Asteroid Mining: Potential Develops, but so do Regulatory, Technical Issues

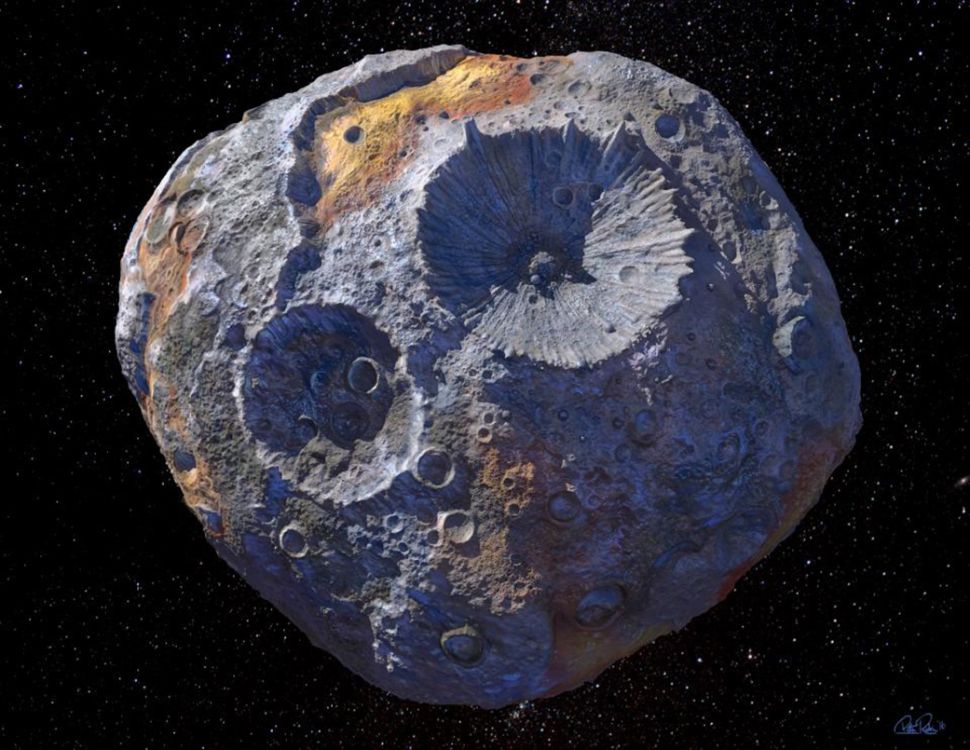

Artist’s concept of the asteroid Psyche, believed rich in nickel and iron, and the focus of a NASA mission that launches this year.

Credit: NASA

Artist’s concept of the asteroid Psyche, believed rich in nickel and iron, and the focus of a NASA mission that launches this year.

Credit: NASA Mankind could soon be able to exploit asteroids to obtain natural resources for use on Earth, gather ingredients for missions in space, and support habitation on the Moon and Mars.1 In the following article, some leading industry experts discuss how to mine in the absence of gravity, how mining could pollute space, and ownership of the resources taken from the asteroids.

Gathering mineral samples from asteroids is no longer science fiction. Japan has its Hayabusa missions; the United States Osiris-Rex. China and Russia have a joint mission planned, and United Arab Emirates has set an ambitious plan for a 2028 mission to the asteroid belt.

In August, NASA plans to launch a probe to explore Psyche-16, a metal-rich asteroid that orbits between Mars and Jupiter. The asteroid has drawn interest since the 1990s when observations, including pictures from the Hubble space telescope, showed it could be the metallic core of a protoplanet. That could mean Psyche-16 offers a bonanza of riches, with some envisioning a Massachusetts-sized block of iron, nickel, and more valuable metals. Some have estimated its worth at $10,000 quadrillion — tens of thousands of times more than Earth’s annual gross domestic product. More recent research found the asteroid may be more rubble pile than a space-based treasure chest. And even if Psyche is as valuable as early assessments suggest, bringing the riches home means a 460-million-mile commute through space with mining equipment that hasn’t been invented. NASA’s probe will take almost four years to reach it.

Rather than seeking fortune in the cosmos, NASA’s Psyche probe could give scientists a look into how planets are formed. The agency said the spacecraft, equipped with cameras, a magnetometer, and a spectrometer to determine what makes up the asteroid, will deliver a “look inside terrestrial planets, including Earth, by directly examining the interior of a differentiated body, which otherwise could not be seen.”

But some on Wall Street see financial potential too enticing to ignore once mankind can mine in space.

By 2023, the Asteroid Mining Corporation plans its first mission. While asteroid mining hasn’t developed as quickly as expected, the future imagined is beginning to take shape. As progress happens on the technological front, many argue the current legal framework in outer space does not sufficiently address the appropriation, extraction, and utilization of space resources. With potential valuations of trillions and quintillion dollars, concerns also have been voiced that the appropriation and excavation of asteroid resources should be regulated to benefit all nations.2

What’s The Greatest Potential For Asteroid Mining?

Christopher Dreyer

The value of asteroid mining depends on the asteroid’s location and the value of the materials it contains, explained Christopher Dreyer, the director of engineering of the Space Resources Center at the Colorado School of Mines. Dreyer studies space objects with an eye on “value chain from resource identification to production of products.”

As in any real estate transaction, asteroid value is tied to location.

“One of the great values of asteroids is that we have them in a location that makes them more usable for the purposes we have in space,” Dryer said. “We don’t have to launch materials on a rocket. We could mine an asteroid and use the materials to construct things in space. I make a distinction between use in space and return to Earth. Returning materials to Earth is often what people think about when you hear about asteroids and asteroid mining. But making a successful business plan where you’re trying to return a valuable resource to Earth, like platinum, for instance, and compete against terrestrial platinum would be challenging.”

Angel Abbud Madrid

Angel Abbud Madrid, who heads the Colorado School of Mines Space Resources Center, said a substance that’s common on Earth is a mining target in space.

“The resources from asteroids are attractive, because first of all, some of them the carbonaceous ones have up to 20-22% of water,” he said. “Water, it’s essential for transportation because you can heat it up and use it as steam, you can separate it into hydrogen and oxygen, which is the most energetic propellant known to humans. You can heat it up to a point of a plasma so then you can use it as another way of propulsion. You can use it for drinking if you have humans around and as a radiation shield, so water is probably one of the most important elements from an asteroid.”

Jamal Rostami

Jamal Rostami, who heads the Earth Mechanics Institute at the Colorado School of Mines and has worked on a NASA project on mining technology beyond Earth, said finding resources in space for use in space make asteroids an attractive mining target.

“What makes asteroids actually attractive is that you don’t have to go there. They come to you,” he said. “If you look at it, in this perspective, people think: ‘Wait a minute, I don’t have to go anywhere. All I have to do is essentially be out there, cast the net, and be able to beam some sort of an exploration system out and look at the components of these asteroids. And if I like what I see, if I like the composition, just go ahead and capture it as it’s coming near you.’ And that’s what makes asteroids very attractive. The fact that they’re coming to you, now that you don’t have to go millions of kilometers or miles to get there.”

What’s The Likely Timeline For Asteroid Mining To Move From Experimental To Routine?

“Timelines are hard to predict, but I think the first uses which could become routine would happen in about 10 years,” Drey- er said. “Beyond that, I think within 20 years, we’d probably be looking at kind of the similar kind of experimental mining of main belt asteroids. And then that becoming routine, the decade after in the 30-year timeframe.”

Tanja Masson-Zwaan

Tanja Masson-Zwaan, deputy director of the International Institute of Air and Space Law at Leiden University, said asteroid mining will likely begin on the Moon.

“I think we are definitely going for using resources in space,” she said. “And water on the moon will be the first thing we will be doing that for various purposes: in-situ utilization. But eventually it will be asteroids, it’s much more complicated. And possibly, at some point, also bringing them back to Earth. But that’s more futuristic than the first steps. It will be incremental.”

How Will Asteroids Be Mined?

The answer from Madrid might be “very carefully.”

“You do not land on an asteroid, you dock to it,” he said. “And so it’s going to be an operation, you have to ground yourself, you anchor yourself. So, you’re going to have to create techniques that are different from the ones that we use here on Earth in order to excavate, to drill, to extract resources. We can no longer use just normal excavators. There’s no traction. And so, you’re going to have to become creative.”

Ian Christensen

The sheer variety of asteroids in space poses a technical challenge for would-be miners, said Ian Christensen, director of private sector programs at the Secure World Foundation.

“On the technical side, I’m not sure that we fully understand the nature of these bodies, these asteroid bodies, and which ones will have extractable resources and which ones won’t,” he said. “And then the types of extraction approaches that will be necessary on different bodies. Because one asteroid may be a rocky pile, another asteroid may be a semi contiguous metal body, and another one, maybe a loosely aggregated pile of dust.”

Rostami said asteroid miners will need to move quickly.

“The greatest challenge in asteroid capture is that asteroids are moving pretty darn fast,” he said. “So, yes, they’re coming towards you, but intercepting an asteroid is going to be quite challenging. If you study dynamics, you realize the concept of inertia, which is mass times velocity squared. …Imagine something moving at a speed of several kilometers per second, because these asteroids are typically the product of collision or product of explosion of planets.”

Mining on Earth has been a messy business that only in the past century has faced clean-up regulations. Masson-Zwaan said those could come early for space miners.

“To avoid errors that we have perhaps made on Earth with mining or other ventures, we should not go for the tragedy of the commons and think things over early on,” she said. “And that also includes the environmental aspects of it.”

Which Asteroids Are Most Likely To Be Mined?

There are more than 20,000 asteroids that roam the solar system in orbits between the Earth and sun. These asteroids are generally separated into different classes according to their composition. Mining effort will focus on M-type (metallic), S-type (stony), and C-type (carbonaceous) asteroids.3 The M-type asteroids are rare but hold precious metals, such as iron that can be used for manufacturing, gold, and metals from the platinum group. S-type asteroids carry other metals, such as nickel and cobalt but also silicate-based metals.4 Water for propulsion, life support, and radiation shields can be extracted from the most common asteroid type, the C-type asteroids.5 Dreyer said these near-Earth asteroids are the most likely targets for mining because they are closest at hand. But that won’t make things easy.

“One example (is the) possibility of finding the right asteroid, the right time, the right type, just passing by Earth when you’re ready to go,” Dreyer said. “If you can’t find the right asteroid for that, you need to spend a fair amount of time traveling to the asteroid, then a long time at the asteroid until orbits match up again, and then return. So there’s kind of these two branches, you either have these particular types of things you can mine over in less than a year, or you have to spend many years mining the asteroid just to deal with the orbital mechanics.”

Far greater than the technical challenge, Madrid said, is the economic one.

“If there is no economic reason for doing this it is not going to happen… If it is just too costly, it’s going to make it very challenging to justify the concept of asteroid mining,” he said.

How Are Asteroid Miners Regulated Now?

No international regulations currently exist on space mining, which led some nations to implement their own regulations. The United States in 2015 implemented the U.S. Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act, which gives businesses and individuals the right to own the resources they mine.6 Luxembourg, Japan, and the United Arab Emirates have since passed similar laws.7

“Their interpretation is there’s no conflict between applicable international law and their national laws that say basically asteroids can be mined,” he said. “The laws basically say their citizens can mine an asteroid, take the material they’ve mined, and then transfer ownership.”

Andreas Losch

Mining operations have been messy on Earth, tearing up the landscape and sowing toxic waste. At the University of Bern in Switzerland, ethics professor Andreas Losch fears asteroid mining could follow a similar path.

“The greatest challenge is not to mess up again, as humankind likes to … and I’m afraid that this is maybe… that we are partially on track to have the wild, wild west scenario again,” he said. “But on the other hand, we have a strong sustainability discussion, and I hope that this discussion will prevail.”

Jinyuan Su

Jinyuan Su, who teaches space law at China’s Wuhan University, said it could take time for laws and treaties to catch up with asteroid mining.

“Law is usually reactive to reality,” he said.

The only international law that currently applies is the Outer Space Treaty, a pact between space- faring nations that prohibited space-based nuclear weapons and blocked nations from claiming territory on the Moon and other celestial bodies. A battle of what space objects could be deemed celestial bodies looms, Su said.

“That’s not a settled question,” he said. “And I think this is a question that we should address in the future.”

If Asteroid Miners Strike It Rich, How Should That Money Be Distributed?

On Earth, mining firms are forced to share the wealth in the form of taxes and fees. Most of the participants interviewed here voiced concern that imposing a structure that would restrict the growth of this sector is the wrong approach. Asteroid mining companies should have the freedom to develop and not be hindered with tax restrictions, which could decrease investor interest needed to mature the industry.

Temidayo Oniosun

Temidayo Oniosun, managing director at Space in Africa and a member of the International Astronautical Federation, holds a different opinion.

“Some are of the opinion that, we should just allow the industry to grow, allow people to do whatever they feel like, and maybe when the industry grows to like a reasonable extent, then they can bring in policies to help them,” he said. “I think that a lot of people think asteroid mining is going to be a win for the entire world. But I don’t think so. Because if even American company goes to mine asteroids, yeah, it’s gonna be in the news and say: ‘Oh, yeah, this is the first time humans will do an asteroid to mine, or whatever’. But I don’t think that is a win for Africa, for example. Neither do I think that’s a way for people in Latin America, or in Southeast Asia.

“For me…if you go to outer space to mine resources, you should use a portion of your revenue you make from that. So fixed fees. And when I say fixed fees, that means to fix the problems of debris. So if a U.S. company goes to space and mine asteroids, let’s say they generate a billion dollars from that. No one is saying they should share the $1 billion with all countries. No. Well, they should be held responsible for certain things like space debris. …This is not just against asteroid mining, this is also applicable to like all space companies that are sending satellites, rockets, and all of it. It’s applicable to all of them. A portion, a tiny portion of whatever revenue these guys are making, should go into research and development that addresses the separate issues.”

Losch agrees there should be international discussion and agreement about fair distribution of resources from space. “Space is international domain, and so it actually belongs to everyone,” he said. “But does that mean everybody can just take everything? That wouldn’t work.”

Masson-Zwaan said while the 1967 treaty requires shared ownership of objects in space, it doesn’t dig into topics like asteroid mining. Because mining in space hasn’t begun, laws on the industry haven’t been written, she said.

“We should also keep an open eye and not try to put everything down in stone from the start,” she said. “Adaptive governance is… a wise approach to such a completely new, very complex, very expensive, very risky business like this is.”

Rostami said regulating a business that still seems more like science fiction than fact poses difficulties.

“I’m hoping that in the next few years, we have a better framework of even thinking about it …,” he said. “But in reality, until and unless some incidents happen, we cannot even think of the laws beforehand.”

How could space mining be regulated?

Some international agreements may provide guidance for space law. Su points to the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources, established by international convention in 1982, and, to lesser success, agreements over international seabeds.

“One of the rationales behind the benefit-sharing argument is that these are the common heritage, common heritage of mankind. And it makes good sense, if we say that the Earth planet is the common heritage of mankind, because we are simply a steward of the planet for our future generations, it would make good sense,” Su said. “But when it comes to outer space, are we also the stewards of the whole universe? Do we all own universe, you know, as a whole species? I believe this is a philosophical question. It’s not, perhaps not purely legal. And people may have very different opinions, and that would come to very different conclusions as to whether there should be benefit sharing or we should follow a free-market approach.”

Corvin Illgner

Corvin Illgner is the co-founder of the SDG 18 initiative “Space for All” and strives for a career in space sustainability. As an intern at Space Foundation, he did research on the topic of fair distribution of asteroid resources, including conducting interviews with the industry leaders quoted in this article.

- Christensen, Ian, Ian Lange, George Sewers, Angel Abbud-Madrid, and Morgan D. Bazilian. “New policies needed to advance space mining.” Issues in Science and Technology 35, no. 2 (2019): 26-30.

- Mallick, Senjuti, and Rajeswari P. Rajagopalan. “If Space is ‘The Province of Mankind’, Who Owns its Resources?” ORF Occasional Papers 182 (2019): 1-26. Accessed May 2021.

- Christensen, Ian, Ian Lange, George Sewers, Angel Abbud-Madrid, and Morgan D. Bazilian. “New policies needed to advance space mining.”

- Shaw, Stephen. astronomysource.com. Aug., 21, 2012. https://astronomysource.com/2012/08/21/asteroid-mining-2/. Accessed May 26, 2021.

- De Sancti s, M. Cristina. “Asteroid smashing, mixing and forming.” Nature Astronomy 5, no. 1 (2021): 9-10.

- “U.S. Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act.” Nov. 25. 2015. https://www.congress.gov/114/plaws/publ90/PLAW-114publ90.pdf. Accessed May 26, 2021.

- Foust, Jeff “Japan Passes Space Resources Law.” June 17, 2021. https://spacenews.com/japan-passes-space-resources-law. Accessed May 26, 2021.