Strikes in Ukraine Spotlight U.S., European Deficits in Hypersonic Arms Race

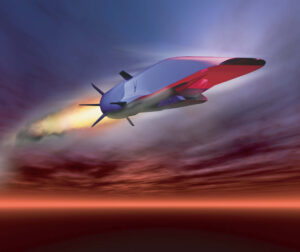

The Pentagon has experimented with hypersonic weapons for decades. An X-51A Waverider successfully launched from a B-52 Stratofortress, like the one shown here, on May 26, 2010. It was the longest supersonic combustion ramjet-powered hypersonic flight to date and accelerated to Mach 6. (U.S. Air Force photo/Mike Cassidy)

The Pentagon has experimented with hypersonic weapons for decades. An X-51A Waverider successfully launched from a B-52 Stratofortress, like the one shown here, on May 26, 2010. It was the longest supersonic combustion ramjet-powered hypersonic flight to date and accelerated to Mach 6. (U.S. Air Force photo/Mike Cassidy)

Russia’s Kinzhal hypersonic missile is shown mounted below a MiG-31 fighter. Credit: Missile Defense Advocacy Alliance

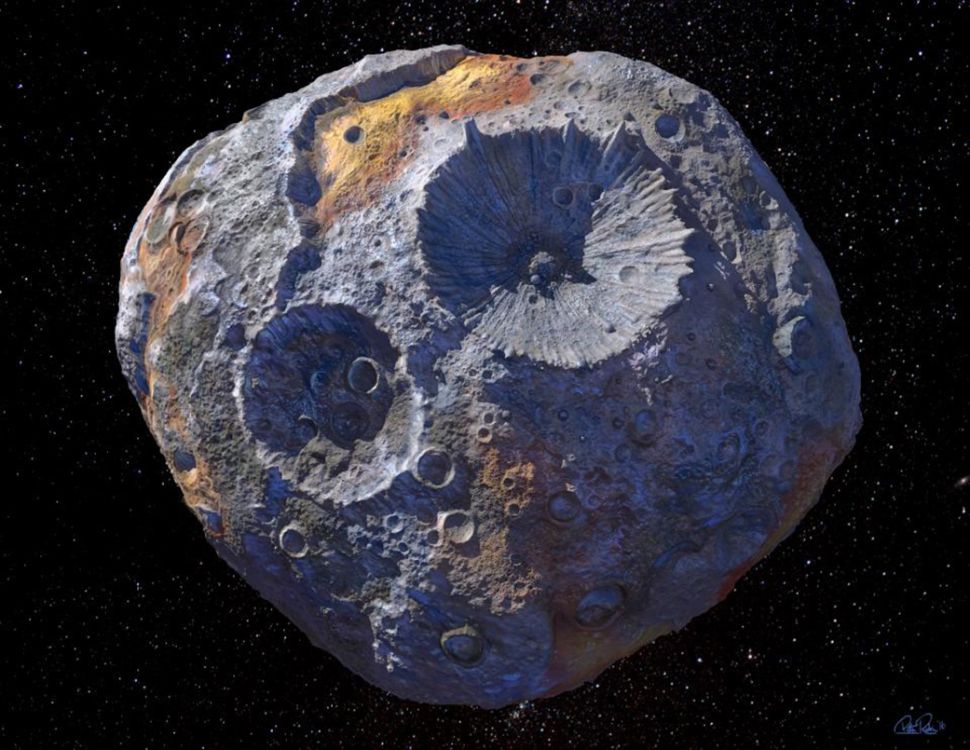

Russia’s use of hypersonic weapons in Ukraine is the latest escalation in a growing arms race for missiles that can travel through the atmosphere at more than Mach 5. The U.S. and its allies are accelerating spending on hypersonic weapons development, but haven’t fielded one to date, prompting leaders to fear a missile gap reminiscent of the Cold War.

Russian hypersonic strikes in Ukraine accelerated efforts around the globe to detect, destroy, and deter the use of such weapons, which can strike with little warning. Hypersonic weapons, which can be armed with explosives or nuclear warheads, fly at more than 3,800 mph — or five times the speed of sound — to streak past existing surveillance systems designed to spot incoming intercontinental ballistic missiles, evading defenses built to knock out cruise missiles and smash warheads at the edge of space.1

Russia’s first publicly acknowledged use of new-generation hypersonic missiles2 wasn’t simply a show of long-range maneuverable weapons capable of slicing through the upper atmosphere at Mach 5 or more. The Russian Kinzhal hypersonic missiles strikes, first announced March 19 and again on May 103, offered a public reminder that regardless of how its war in Ukraine has stalled, Russia and China possess hypersonic missiles, including weapons capable of packing nuclear warheads, while the United States and its allies remains years behind.

Despite years of testing hypersonic vehicles like this X-51 Waverider, leaders say the U.S. is years behind its rivals in the technology. Credit: NASA

A 2017 Rand Corp. study found the combination of stealth and speed gives leaders as little as six minutes warning to react to a hypersonic attack. That’s about a quarter of the warning time leaders would have for an incoming ICBM strike.4 Some researchers believe that such a short warning window could lead nations to resort to “a launch-on-warning posture — a hair-trigger tactic that would increase crisis instability.”5

Experts say the U.S. is as much as three years away from matching the Russian capability. It’s a situation that alarms leaders because stealthy hypersonic weapons fly below sensors used to detect ballistic missiles and at speeds 10 times faster than traditional cruise missiles.

The weapon used in Ukraine, Russia’s Kinzhal, has a range of more than 1,200 miles and can fly at speeds of more than 7,000 mph, according to the Virginia-based Missile Defense Advocacy Alliance — putting it within range of NATO headquarters in Brussels, Belgium, or other major European cities. If launched over the Atlantic Ocean, the Kinzhal could target America’s Eastern Seaboard.

Kinzhal, like some other hypersonic missiles, can pack the conventional warhead used in Ukraine, or thermonuclear warheads that could destroy entire cities.6 Another factor in the equation: Russia and China have issued hypersonic weapons to military units, while similar American systems are still on the drawing board, said Iain Boyd, who heads the Center for National Security Initiatives at the University of Colorado at Boulder.7

Military leaders have warned hypersonic missiles threaten the delicate balance of strategic deterrence that has prevented nuclear conflict since World War II.8 Even during the buildup of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, U.S. defense leaders were concerned. In early February, Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin convened top Pentagon officials and defense industry executives to discuss the impediments to developing hypersonic capabilities.9

After the Kinzhal strikes, some defense leaders examined larger motives for the use of hypersonics in Ukraine. The United Kingdom Ministry of Defense on March 21 contended that the first combat use of hypersonic weapons wasn’t driven solely by military necessity.

“Russian claims of having used the developmental Kinzhal is highly likely intended to detract from a lack of progress in Russia’s ground campaign,” the ministry stated.10

Even though the weapons made little noticeable difference in the Ukraine War, their use triggered American leaders to express concern that rival powers have a technical edge in strategic weapons for the first time since the Cold War.

“It’s — as you all know, it’s a consequential weapon,” President Joe Biden warned in a March 21 news conference confirming the hypersonic strike.11 “And … with the same warhead on it as … any other launched missile. It doesn’t make that much difference, except it’s almost impossible to stop it.”

NORAD Gen. Glen VanHerck

Two weeks before the Russian hypersonic attack, North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) leader Gen. Glen VanHerck told a congressional panel that China also holds a long lead in hypersonic technology.12

“They’re aggressively pursuing hypersonic capability tenfold to what we have done as far as testing within the last year or so, significantly outpacing us with their capabilities,” VanHerck told the House Armed Services Committee panel on strategic forces.

Colorado U.S. Rep. Doug Lamborn, the ranking Republican on the House Armed Services Strategic Forces Panel, said America faces a missile gap reminiscent of the most frigid epoch of the Cold War.13

“When you think about hypersonics, we don’t even have a defense against that,” Lamborn said. America’s rivals have found U.S. vulnerabilities and plan to exploit them, he said. “Frankly, Russia and China have been working day and night,” he said. “They know where the seams in our defenses are. They are not resting, and we cannot rest, either.”

It’s more than Russia and China. North Korea boasted of its Sept. 22 test of a new hypersonic weapon through the government-run Korea Central News Agency.14

“The development of this weapon system, which has been regarded as a top priority work under the special care of the Party’s Central Committee, is of great strategic significance in markedly boosting the independent power of ultra-modern defense science and technology of the country and in increasing the nation’s capabilities for self-defense in every way,” the news agency said.

Other international actors researching and testing hypersonic weapons include India, Australia, Japan, France, the United Kingdom, Germany, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan, Canada, Pakistan, and Brazil.15 India’s program, a joint effort with Russia, is planned to counter threats from China and Pakistan. The Indian missile program allegedly triggered an international incident in March when an unarmed test vehicle went off course and landed in Pakistan.16

First Sea Lord Adm. Ben Key

Britain’s Royal Navy is chasing hypersonic technology as a method to make a small fleet pack more punch.

“The geopolitical tectonic plates are moving, as we shift from the large land centric campaigns of the last 20 years,” First Sea Lord Adm. Ben Key said in a February speech. “It feels as if we are returning to a maritime era…”

And the Royal Navy, which once served as Britain’s “wooden walls” in the days of sail, sees high-tech weaponry as its best bet to combat possible threats from nations including Russia and China.

“It’s a future where we are setting ourselves a challenge to become a global leader in hypersonic weapons,” Key said. “A future where we’ll become more adaptive in how we use our platforms, high end war fighting, command and control, floating embassies for the United Nations. Highly lethal, highly reassuring, and highly adaptable.”17

America, Allies Seek New Systems to Detect, Destroy Hypersonic Weapons

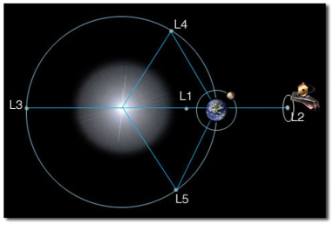

America has the tools to defend itself against most missile threats, but hypersonic weapons present new challenges that even the U.S. Space Force’s Space-based Infrared System satellites, capable of spotting the heat from intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) launches, are not yet equipped to handle.18, 19 The United States and its European allies have multiple hypersonic missile interceptor programs in development, but as both continents lack dedicated defenses to hypersonic weapons, several nations are rushing to develop satellites and ground systems to better detect and target hypersonic weapons in flight.

In the United States, the Navy’s SM-6 is the only missile that offers “nascent capability” to counter a hypersonic missile, according to Missile Defense Agency leader Vice Adm. Jon Hill.20 Even that assessment has its skeptics, who deem the SM-6 too slow.

U.S. Rep. Jim Cooper, D-Tenn., chided military leaders during a May 11 hearing for not more aggressively pursuing more futuristic systems, including lasers.21

“I hope that we are not shortchanging the chance for a directed-energy breakthrough because of the terrific promise of that technology,” Cooper said.

Leaders in the U.S. are looking at more conventional solutions, including a partnership with Israel to drive development of the Arrow-4 interceptor missile.22 Hill told Cooper’s subcommittee the MDA is looking at new ways to counter the weapons by integrating data from sensors in space with defense systems on the ground. That would bring a variety of weapons, from interceptor missiles like the Patriot, Arrow, and SM-6 into play with an integrated command system matching the right weapon to the target.

“MDA is developing a system that is agile and resilient to deter, deny and defeat missile threats,” Hill told lawmakers. “This requires the ability to globally view, track, and engage threat missiles using a multispectral, real‐time, persistent, and survivable sensor architecture”

- To accomplish that goal, the Pentagon and allies are developing several defensive weapons:

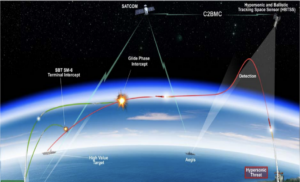

- The United States is developing a hypersonic defense program through the MDA in partnership with the Space Development Agency, the Army’s Space and Missile Defense Command, and the Space Force. One piece of the new system is the Hypersonic and Ballistic Tracking Space Sensor (HBTSS), a planned constellation of satellites to track hypersonic missiles and relay data to leaders and ships equipped with the Aegis Combat System and Standard surface-to-air missiles, which can target the incoming threats. L3Harris and Northrop Grumman were the two finalists for the project, and both defense contractors announced in 2021 that their prototypes would be scheduled to launch in 2023.23, 24

- In Germany, missile giant MDBA has plans to protect Europe from hypersonic threats under a contract backed by European Union nations.25 The new endo-atmospheric interceptor will address a wide range of threats including maneuvering ballistic missiles with intermediate ranges, hypersonic or high-supersonic cruise missiles, hypersonic gliders, anti-ship missiles and more conventional targets such as next-generation fighter aircraft, MDBA officials have stated.

- Israel Aerospace Industries, Lockheed Martin, and Raytheon are also working on new tools to defeat hypersonic weapons.26 New technologies, such as high-energy lasers, are being mulled as solutions.27 Laser weapons already can defeat drones but developing a weapon with sufficient photon capacity to fry a ballistic missile is a challenge not yet solved, Raytheon has stated. Once engineers find a clean, practical, and efficient way to produce that power, they will also need to focus it into an ultra-precise beam. The lasers might need to be mounted to aircraft or satellites to ensure a clear shot.

Progress on defense measures is the top priority, said Col. Doug Wickert, who heads the Air Force Academy Department of Aeronautics and is leading one research effort on hypersonic missiles.

“We probably don’t need much of an offensive capability, we have a lot of arrows in our quiver,” he said. “Understanding hypersonics and being able to defend against it is more important in the near term.”

Defensive capabilities become more important given the Russian and Chinese ability to equip hypersonic missiles with nuclear warheads. During his Senate Armed Services testimony, NORAD’s VanHerck warned that hypersonic weapons threaten his ability to provide adequate warning of an incoming nuclear attack.

“Weapons such as these are designed to circumvent the ground-based radars … to detect and characterize an inbound threat and challenge my ability to provide threat warning and attack assessment,” the general told senators. “The impact is the loss of critical decision space for national-level decision-makers regarding continuity of government and the preservation of retaliatory capabilities, resulting in an increase in the potential for strategic deterrence failure.”

Lt. Gen. Daniel Karbler, who heads the Army’s Space and Missile Defense Command, told a House committee that defeating an enemy’s missile capabilities will require more than satellites and interceptors. He called for the military to use all its tools, including taking out hypersonic systems prior to launch if America is attacked.28

“Adversary offensive missile and hybrid systems are increasingly complex and challenging in their delivery means and scale,” he told lawmakers. “As such, an optimal missile defense requires both defensive and offensive capabilities to defeat potential threats.”

This artist’s rendering shows how a planned constellation of satellites to track hypersonic weapons would allow naval assets to intercept them in flight. Credit: Missile Defense Agency

New Challenges, New Partners in Hypersonic Race

What makes hypersonic missiles deadly, Boyd said, is that they can fly fast at very high or low altitudes and quickly change course. That means they can fly above the coverage of fighter jets or duck down below radar range to deliver destruction, while giving opponents just minutes or seconds to react. Russia’s Kinzhal is powered by a solid rocket booster that accelerates to Mach 10 before it burns out and the weapon glides to its target. The glide vehicles are small and stealthy, making them difficult to track on radar.29 They can also be hard to hit with heat-seeking missiles because they cool down substantially while gliding after their boost phase.30

Russian defense ministry officials in December announced through the Russian news agency TASS that a Zircon hypersonic missile had been launched at sea. Credit: TASS

Russia’s hypersonic Kinzhal missiles apparently evaded Ukraine’s extensive air defense systems, which include the S-300 long range missile system, the Buk medium range missile system, and the handheld Stinger short-range missile.31

Other hypersonic weapons, including Russa’s Zircon missile, use jet engines to power them all the way to their target, increasing the weapon’s range.32 They’re designed to evade defenses by sheer speed and maneuverability.33 All of them can be difficult to track with existing technology, but Pentagon leaders are hopeful the experimental HBTSS satellites, due for launch in 2023, will be able to spot them. The Pentagon stated the new satellites are designed “to ensure dim targets, meaning cruise missiles, can be pinpointed from space.”34

Meanwhile, America’s weapons development efforts have moved slowly, in part because the U.S. has lacked capacity for large-scale hypersonic wind tunnel studies, a problem that has prompted warnings from industry groups for nearly two decades.35 The Defense Department has invested in new facilities and research work at more than 90 colleges and universities through its University Consortium for Applied Hypersonics, which was established by Congress in 2020.36 The effort includes building several new hypersonic wind tunnels and computer simulation facilities.37

The U.S. Navy released this rendering of its proposed hypersonic weapon, the Conventional Prompt Strike. Credit: Navy

“Our focus is not just to leapfrog our competitors, but to leap far ahead where our capabilities will be unmatched and not easily imitated,” Gillian Bussey, director of the Pentagon’s Joint Hypersonic Transition Office, told a conference of the university consortium’s members in March.38

With this collegiate collaboration, however, comes another issue that has slowed communication and progress. The colleges are paired with federal partners including the Air Force Office of Scientific Research, the Air Force Research Laboratory, Army Futures Command, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), NASA, and the Office of Naval Research. University leaders and top military officials have warned that partnerships to build American hypersonic weapons and deter rivals with hypersonic weapons is hampered by the Pentagon’s penchant for secrecy.39 Former Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, retired Air Force Gen. John Hyten, has long warned that secrecy slows innovation and hamstrings America’s ability to deter rivals including Russia and China by unveiling American combat capabilities. Hyten joined the Space Foundation Board of Directors in April.

“We’re going to have to change the classification structure that we have,” he said during an Oct. 28 speech at George Washington University in Washington, D.C.40 “Not to declassify everything. That would be foolish. But it’s so highly classified now that you can’t talk about anything. And that’s a mistake.”

Despite difficulties, the Pentagon has continued to attack the hypersonic problem, and increasingly, is harnessing the power of smaller firms in the effort.41 Most of the small- and medium-sized businesses in the sector focus mainly on one aspect of production, whether it be the engine, fuel, or other component. Ursa Major Technologies, an aerospace propulsion company, ventured into the realm of hypersonics to fabricate engines through 3D printing. In March, Ursa Major delivered its first two hypersonic engines and announced it is in full production to deliver 30 of them this year.42 Another company, Spectral Energies, in 2021 received an Air Force grant for accurate wind-tunnel tests to be conducted at speeds up to Mach 18.43

HACM. Artist’s rendering of the HAWC hypersonic weapon. Credit DARPA

- The program to bring U.S. hypersonic weapons to troops has tight timelines.

- The Army wants a prototype of its Long Range Hypersonic Weapon in 2023.44 With a range of more than 1,700 miles and capable of topping 3,800 mph, the Army says it will “provide a critical strategic weapon and a powerful deterrent against adversary capabilities.”45 The Army is already training crews for the “Dark Eagle” missile, with ground equipment sent to Germany ahead of fielding the weapon.46

- The Navy plans its Conventional Prompt Strike hypersonic weapons system to be loaded aboard ships by 2025.47

- In early April, the U.S. Air Force announced that its Air-Launched Rapid Response Weapon (ARRW), a hypersonic missile designed to be launched from bombers, would be delayed for up to a year following “flight test anomalies” during booster motor tests.48 In 2023 budget proposals, the service cut planned spending on that weapon to $46 million.49 In mid-May, the Air Force announced a second, successful test of the missile.50

- The Air Force has another hypersonic missile in development, the Hypersonic Attack Cruise Missile, or HACM.

- With $200 million spent on HACM development in 2022, the Air Force expects to carry it aboard its planes in 2026.51

- DARPA may have the most promising program with its Hypersonic Air- Breathing Weapons Concept, the HAWC, which had a successful test flight April 5.52 DARPA is also working on a weapon called Tactical Boost Glide, “to develop and demonstrate technologies to enable future air-launched, tactical-range hypersonic boost glide systems.”53 DARPA is also developing “Operational Fires,” a shorter-range ground-based hypersonic weapon that gets its speed from a two-stage rocket.54

The Pentagon’s 2023 budget proposal includes $7.2 billion for “long-range fires,” a category that includes hypersonic weapons. The Pentagon confirmed plans to field a ground-launched hypersonic weapon by 2024, with sea- and air-launched systems to follow.55

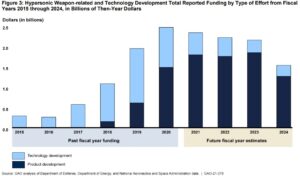

The Government Accountability Office estimates U.S. spending on hypersonic weapons development could hit $15 billion by 2024. Credit: GAO

The Government Accountability office in 2021 estimated U.S. investments in hypersonic vehicle programs could top $15 billion by 2024.56 Before the House Armed Services Committee on March 8, VanHerck said American hypersonic efforts are gathering steam.

“We’re picking up in that department,” he said. “I’m confident … when the budget comes out, we’ll see additional resources applied into the hypersonic area as well as in threat warning and attack assessment for those capabilities.”

America Lost Long Lead, May Have Triggered Hypersonic Race

The Cold War drove rapid development of U.S. hypersonic programs in the 1950s, before they were tossed aside in favor of intercontinental ballistic missiles. Rocketed to space for a ballistic trip to their targets, ICBMs presented fewer problems than hypersonic weapons, which must transit atmospheric friction for their high-speed flight, leading to extreme heat.57

Air Force Academy cadets tested this wind tunnel model of NASA’s Bolt II. Credit: NASA

Starting in the 1950s, American metallurgists and chemists labored for the perfect heat shield. NASA’s X-15, the first winged craft to hit hypersonic speeds, was fabricated using a special high-strength nickel alloy named Inconel X, designed to withstand temperatures of 1,200 degrees, as hot as the lava spewed from Hawaiian volcanoes58. The Air Force’s X-20 Dyna-Soar, a crewed space plane designed to skip through Earth’s upper atmosphere after launch atop a Titan missile, had a nose cone made from graphite and synthetic diamonds planned to withstand temperatures approaching 5,000 degrees. That’s hot enough to boil aircraft aluminum to vapor.59

Decades later, America is rediscovering ways to overcome the problems that accompany flight at hypersonic speeds. At the Air Force Academy, Wickert and a team of cadets and researchers have used the school’s hypersonic wind tunnel to help NASA design its Bolt II hypersonic research vehicle.60 The research probed the turbulence when vehicles transition to hypersonic speeds. Similar to breaking the sound barrier, which puts vehicles through a turbulent wave of pressure, hypersonic vehicles fly through a “boundary layer,” which lashes airframes with friction, causing extreme heating like that of meteors entering Earth’s atmosphere.61 While meteors decelerate as the descend, hypersonic vehicles are designed to accelerate and fly in the friction-filled boundary.

“The longer you are in it the hotter and hotter you will get,” Wickert explained.

While scientists tackle the heat, policymakers are trying to figure out how America wound up trailing in the hypersonic race. One leading theory is that America’s rivals began aggressively pursuing hypersonic weapons after the U.S. rendered other nation’s stockpiled ICBMs obsolete in the early 2000s. That gave rival nations a two-decade head start on hypersonics as America focused on technology for warfare in Iraq and Afghanistan.

The United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research found that the hypersonic weapons programs of Russia and China sprouted after the United States in 2002 backed out of 1967’s Anti- Ballistic Missile Treaty in favor of fielding a missile shield.62

An interceptor designed to take out incoming nuclear warheads is placed in its Alaska silo. Credit: Defense Department

The accord reached between the U.S. and Soviet Union in 1967 had placed limits on anti-missile systems.63 The two sides reasoned in the late 1960s that limiting defensive systems would reduce the need to build more or new offensive nuclear missiles.64

After President George W. Bush dropped the treaty, the Army began fielding its ground-based mid-course missile defense system in 2003, with interceptors based in Alaska and California to knock down nuclear warheads from ICBMs.65 A year later, the Navy unveiled its own ICBM defense system, with interceptors that can be launched from ships or shore installations.66

The missile shield was touted as protection against weapons fired by rogue states and terrorists. 67 It also could shoot down nuclear-tipped ballistic missiles from Russia and China. “Relevant states appear to be at least in part motivated by the pursuit of this (hypersonic) technology by rivals, as well as the pursuit or possession of other strategic technologies — in particular missile defenses,” the U.N.’s Institute for Disarmament Research found.68

Diplomatic Accord Could Curb Hypersonic Arms Race

In the past, revolutionary weapons have prompted international agreements to curb their use. The Dreadnought-class battleship that took to the seas in the 1900s eventually drove the London Naval Treaty, which aimed at limiting a global naval arms race like the one that receded World War I.69

This 1963 United Nations panel pushed for adoption of what later became the Outer Space Treaty. Credit: United Nations

American orbital bomber proposals of the 1960s and envisioned military space stations studded with nuclear weapons united the world for an accord to ban space-based nuclear weapons reminiscent of some hypersonic missiles.70 The U.N.’s 1968 Nonproliferation Treaty was designed to stop the spread of nuclear weapons to non-nuclear nations, including India, Pakistan, and North Korea, which eschewed the treaty to develop atomic warheads.71

Less than a decade after the 1957 launch of Russia’s Sputnik, the first manmade satellite, the United Nations brought the United States, the Soviet Union, and the United Kingdom to the table where they agreed to the 1967 Outer Space Treaty.72 The accord included a provision that nations “shall not place nuclear weapons or other weapons of mass destruction in orbit or on celestial bodies or station them in outer space in any other manner…”

Hypersonic weapons, including those fielded by China, skirt the edge of space and maneuver around treaties with “fractional orbit bombardment,” which sends the vehicles to the edge of space before they maneuver to their target before completing an orbit of the planet.73 Laura Grego, Stanton Nuclear Security Fellow at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Laboratory for Nuclear Security and Policy, explained that there is a “…legal analysis which suggests that as long as you don’t complete one entire orbit, you haven’t contravened your obligations of the Outer Space Treaty.”74

The UN is holding out hope it can broker a new pact to limit hypersonic weapons.75 But, without Russian and Chinese support, the effort has gained little traction.

“Strategic arms control is in crisis,” the UN stated in 2019. “Despite the clear benefits of cooperative arms limitation endeavors, some influential actors have seemingly turned away from this concept as the surest way to achieve security.”

China’s touting of its hypersonic weapons, including a series of tests and displaying hypersonic missiles in a military parade, is the latest saber-rattling move for a nation that is increasing its global influence along with its nuclear stockpiles.76

China’s People’s Liberation Army parades DF-17 hypersonic missiles through Beijing in 2019. Credit: Chinese Ministry of Defense

“What is very clear is that China is pushing to develop its nuclear capabilities — its strategic intercontinental capabilities — significantly beyond what has been the case for the last four decades … five decades,” The Heritage Foundation, a Washington think tank, noted.

China, meanwhile, has derided U.S. efforts to counter its acknowledged hypersonic program, calling America the “true destroyer of regional and global peace and stability” in an April editorial published in the state-run People’s Daily. Russia has called hypersonic weapons the “backbone” of its national defense.77

“The potential of non-nuclear deterrence forces, primarily, precision weapons, is being strengthened. Hypersonic systems of various basing will comprise their backbone,” Russian Defense Minister Army General Sergei Shoigu stated according to the state-run news agency TASS.

At the University of Colorado, Boyd said an all-out hypersonic arms race between the world’s major powers could prove costly even for the Pentagon, which was set to spend $2 billion a day under a budget accord reached in March.78

“We’re talking hundreds of billions of dollars,” he said.

Despite increasingly frosty relations between the United States, China, and Russia, Boyd believes the best American solution for hypersonic missiles may come from compromise and diplomacy rather than spending and science.

“We need a treaty,” he said. “We need Russia and China to come to the table.”

Such a step happened little more than a year ago. On Feb. 3, 2021, Secretary of State Anthony Blinken announced the U.S. and Russia agreed to an extension of 2011’s New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty with Russia, keeping the agreement that limits nuclear weapons in both nations through 2026.79

Blinken also pledged future negotiations with China on strategic weapons, including hypersonic missiles.

“We will also pursue arms control to reduce the dangers from China’s modern and growing nuclear arsenal,” Blinken said. “The United States is committed to effective arms control that enhances stability, transparency and predictability while reducing the risks of costly, dangerous arms races.”

In a 2021 address, Secretary of State Anthony Blinken told the United Nations that America was ready to work with Russia and China on arms control. Credit: State Department

Director-General of China’s Department of Arms Control of the Foreign Ministry Fu Cong issued a statement Jan. 4 that signaled Beijing’s willingness to discuss arms control if Russia and other nuclear powers including the United Kingdom, the United States and France join in.80

“The Chinese side believes that the five nuclear-weapon states should further strengthen communication on strategic stability and conduct in-depth dialogues on reducing the role of nuclear weapons in national security policies and a wide range of topics including anti-missile, outer space, cyberspace and artificial intelligence,” Cong said in a statement. “China stands ready to continue to strengthen communication and coordination with the other four states, enhance strategic mutual trust and play a leading role in building a world of lasting peace and universal security.”

But with global tensions on the rise amid the war in Ukraine, more nations are joining the race to perfect hypersonic weapons. Ursula von der Leyen, who presides over the European Union’s governing commission, said the 27 members of the international body are joining forces to combat new threats.81

“Against the backdrop of deepening geopolitical rivalries, the European Union must maintain its technological edge,” she said. “It can do so by addressing the wide range of threats, from conventional to hybrid, cyber and space, and can build the necessary scale through joint development, joint procurement and a convergent approach to exports. In addition to ensuring the security of EU citizens, the European defense sector can contribute to the economic recovery through positive innovation spill-overs for civilian uses.”

On March 24, NATO leaders, including Biden, met in Belgium and pledged a joint effort to address emerging threats, including hypersonic weapons.82

Leaders of NATO nations gathered in Belgium on March 24 and pledged more resources to address emerging threats including hypersonic missiles. Credit: NATO

“We will now accelerate NATO’s transformation for a more dangerous strategic reality, including through the adoption of the next Strategic Concept in Madrid,” the leaders said in a joint statement, referencing a planned June meeting in Spain that will set a new strategic agenda for the alliance. Leaders pledged to boost budgets to obtain the new weapons needed to counter growing threats. It is the biggest defense boost Europe has seen since the height of the Cold War, pushing global defense budgets to a record $2 trillion.83

“In light of the gravest threat to Euro-Atlantic security in decades, we will also significantly strengthen our longer-term deterrence and defense posture and will further develop the full range of ready forces and capabilities necessary to maintain credible deterrence and defense.”

Gabriel Flouret is a Space Foundation intern and contributing writer. In June, he will participate in the NORAD and USNORTHCOM Volunteer Student Internship Program in Colorado Springs, CO. Previously, he worked at Ursa Major Technologies.

Tom Roeder is a Space Foundation senior research analyst and editor who has spent nearly three decades covering aerospace and national security topics. He can be reached at troeder@spacefoundation.org

Tom Roeder is a Space Foundation senior research analyst and editor who has spent nearly three decades covering aerospace and national security topics. He can be reached at troeder@spacefoundation.org- Tiron, Roxanna. “Hypersonic Weapons: Who Has Them and Why It Matters.” April 6, 2022. Bloomberg News via Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/hypersonic-weapons-who-has-them-and-why-it-matters/2022/04/05/1f6d0280-b557-11ec-8358-20aa16355fb4_story.html. Accessed April 21, 2022.

- TASS. “RF Armed Forces Destroyed Underground Ammunition Depot of Armed Forces of Ukraine with Kinzhal Hypersonic Missiles.” March 19, 2021. https://tass.ru/armiya-i-opk/14122149. Accessed March 19, 2022. Tucker, Patrick. “Russia Has Fired ‘Multiple’ Hypersonic Missiles into Ukraine, U.S. General Confirms.” Defense One. March 29, 2022. https://www.defenseone.com/threats/2022/03/russia-has-fired-hypersonic-missiles-ukraine-us-general-confirms/363777. Accessed March 30, 2022.

- Lendon, Brad. CNN. “What to know about hypersonic missiles fired by Russia at Ukraine.” May 10, 2022. https://www.cnn.com/2022/03/22/europe/biden-russia-hypersonic-missiles-explainer-intl-hnk/index.html. Accessed May 10, 2022.

- Blair, Bruce. “The U.S. Nuclear Launch Decision Decision Process.” https://www.globalzero.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Full-LOWTimeline.pdf. October 2019. Access May 18, 2022.

- Speier, Richard H., et al. “Hypersonic Missile Nonproliferation.” 2017. https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR2100/RR2137/RAND_RR2137.pdf. Accessed April 1, 2022.

- Missile Defense Advocacy Alliance. “Kh-47M2 Kinzhal.” June 28, 2018. https://missiledefenseadvocacy.org/missile-threat-and-proliferation/todays-missile-threat/russia/kh-47m2-kinzhal-dagger/. Accessed March 22, 2022

- Interview with Iain Boyd, March 21, 2022

- VanHerck, Gen. Glen. Statement of Gen. Glen D. VanHerck, United States Air Force. Command U.S. Northern Command and North American Aerospace Defense Command. March 24, 2022. https://www.armed-services.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/USNORTHCOM%20and%20NORAD%202022%20Posture%20Statement%20FINAL%20(SASC).pdf. Accessed March 24, 2022.

- Albon, Courtney and Gould, Joe. “Top Pentagon Officials Met with Industry Executives about Hypersonics. What Comes Next?” Feb. 4, 2022. Defense News. Accessed March 22, 2022.

- United Kingdom Ministry of Defense, “Update on Ukraine.” March 21, 2022, https://twitter.com/DefenceHQ/status/1506031949386813446/photo/1. Accessed March 22, 2022.

- The White House, “Remarks by President Biden Before Business Roundtable’s CEO Quarterly Meeting.” March 21, 2022. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/speeches-remarks/2022/03/21/remarks-by-president-biden-before-business-roundtables-ceo-quarterly-meeting/. Accessed March 23, 2022.

- House Armed Services Committee: “HASC-SF Subcommittee Hearing Fiscal Year 2023 Strategic Forces Posture Hearing.” March 1, 2022. https://www.stratcom.mil/Media/Speeches/Article/2959753/hasc-sf-subcommittee-hearing-fiscal-year-2023-strategic-forces-posture-hearing/. Accessed March 23, 2022.

- Lamborn, Doug. Interview with Author. Feb. 22, 2022

- Korea Central News Agency. “Hypersonic Missile Newly Developed by Academy of Defence Science Test-fired.” Sept. 29, 2021. https://kcnawatch.org/newstream/1632870069-293810660/hypersonic-missile-newly-developed-by-academy-of-defence-science-test-fired/. Accessed March 22, 2022

- Davis, Susan. “Hypersonic weapons – a technological challenge for allied nations and NATO?” June 18, 2020. https://www.nato-pa.int/download-file?filename=sites/default/files/2020-07/039%20STC%2020%20E%20-%20HYPERSONIC%20WEAPONS.pdf. Accessed March 25, 2022.

- Voice of America, “Military: Pakistan Hit by ‘Unarmed Supersonic Missile’ Allegedly Fired by India” March 10, 2022. https://www.voanews.com/a/military-pakistan-hit-by-unarmed-supersonic-missile-allegedly-fired-by-india-/6479682.html. Accessed March 30, 2022.

- Royal Navy. “Admiral Sir Ben Key’s speech to industry leaders in Rosyth.” Feb. 11, 2022. https://www.royalnavy.mod.uk/news-and-latest-activity/news/2022/february/11/20220211-speech-by-1sl. Accessed May 18, 2022.

- Space Force. “Space Based Infrared System.” March 22, 2017. https://www.spaceforce.mil/About-Us/Fact-Sheets/Article/2197746/space-based-infrared-system/. Accessed March 21, 2022.

- Space Force. “PAVE PAWS Radar System.” March 22, 2017. https://www.spaceforce.mil/About-Us/Fact-Sheets/Article/2197752/pave-paws-radar-system/. Accessed March 21, 2022.

- Burgess, Richard R. Seapower. “Vice Adm. Hill: MDA Pushes Space-based Sensor for Tracking Hypersonic Missiles for Fleet Defense.” Feb. 2, 2022. https://seapowermagazine.org/vice-adm-hill-mda-pushes-space-based-sensor-for-tracking-hypersonic-missiles-for-fleet-defense. Accessed May 9, 2022.

- Opening Statement of U.S. Rep. Jim Cooper, chairman of the Strategic Forces Subcommittee of the House Armed Services Committee. May 11, 2022. https://mailchi.mp/3be345c155e3/may11-str-hearing-8955797?e=c1048d4e88. Accessed May 11, 2022.

- Testimony of Vice Adm. John Hill before the House Armed Services Committee, May 12, 2022. https://armedservices.house.gov/_cache/files/4/f/4ff340b3-e1a6-436c-99b8-18db4cea4089/2BFBA2F9187724987A3A950972410120.20220511-str-witness-statement-hill.pdf. Accessed May 12, 2022.

- L3Harris. “L3Harris Completes Final U.S. Missile Defense Agency Satellite Design Milestone.” Dec. 20, 2021. https://www.l3harris.com/newsroom/press-release/2021/12/l3harris-completes-final-us-missile-defense-agency-satellite-design. Accessed March 25, 2022.

- Northrop Grumman, “Counter Hypersonics Mission.” Undated. https://www.northropgrumman.com/space/counter-hypersonics/. Accessed March 25, 2022.

- MDBA. “MDBA Ready to Meet Challenge of Europe’s Missile Defence.” Nov. 13, 2019. https://www.mbda-systems.com/press-releases/mbda-ready-to-meet-the-challenge-of-europes-missile-defence/. Accessed March 25, 2022

- Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs. “Flight test of the Arrow 3 weapon system successfully completed.” Jan. 18, 2022. https://www.gov.il/en/departments/news/flight-test-of-arrow-3-weapon-system-successfully-completed-18-jan-2022. Accessed March 25, 2022.

- Raytheon Technologies. “Laser Missile Defense.” Sept. 9, 2019. https://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:VIGCi46oAKQJ:https://www.raytheon.com/news/feature/moonshot-lasers-kill-missiles+&cd=1&hl=en&ct=clnk&gl=us. Accessed March 25, 2022.

- Testimony of Lt. Gen. Daniel Karbler before the House Armed Services Committee, May 12, 2022. https://armedservices.house.gov/_cache/files/d/e/dee1d7ca-23c0-4dd0-9207-a8803c9e8857/094C7DAE7B31E2A86783A4B6258EF2F1.20220511-str-witness-statement-karbler-.pdf. Accessed May 13, 2022.

- CSIS Missile Defense Project. “Kh-47M2 Kinzhal.” March 19, 2022. https://missilethreat.csis.org/missile/kinzhal/. Accessed May 13, 2022.

- Wright, David. “Heat Conduction into a Hypersonic Glide Vehicle.” Nov. 20, 2020. https://lnsp.mit.edu/s/Wright-Heat-conduction-into-a-hypersonic-glide-vehicle_11-12-20.pdf. Accessed May 13, 2022.

- Royal United Services Institute. “Ukrainian Air Defense Options in the Event of Russian Attack.” Feb. 8, 2022. https://rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/commentary/ukrainian-air-defence-options-event-russian-attack. Accessed May 13, 2022.

- Missile Defense Advocacy Alliance. “3M22 Zircon” Undated. https://missiledefenseadvocacy.org/missile-threat-and-proliferation/todays-missile-threat/russia/3m22-zircon/. Accessed March 30, 2022.

- TASS. Zircon Hypersonic Missile Trials to Wrap Up in 2021. Jan. 29, 2021. https://tass.com/defense/1250443. Accessed May 13, 2021.

- Defense Department. “DOD Focused on Hypersonic Missile Defense Development, Admiral Says.” May 13, 2022. https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/3028518/dod-focused-on-hypersonic-missile-defense-development-admiral-says/. Accessed May 13, 2022.

- American Institute for Aeronautics and Astronautics. “Critical Need for Continuing Operation of U.S. National Wind Tunnel Facilities.” April 16, 2007. https://www.aiaa.org/docs/default-source/uploadedfiles/issues-and-advocacy/aeronautics/wind-tunnel-wp-041607.pdf?sfvrsn=e0230f1b_0. Accessed May 13, 2022.

- University Consortium for Applied Hypersonics. “Membership.” May 2022. https://hypersonics.tamu.edu/membership/ Accessed May 13, 2022.

- Department of Defense. “DOD Awards Applied Hypersonics Contract to Texas A&M University.” Oct. 26, 2020. https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/2394438/dod-awards-applied-hypersonics-contract-to-texas-am-university/. Accessed March 24, 2022.

- University Consortium for Applied Hypersonics. “Spring Forward, Leaping Ahead.” April 6, 2022. https://hypersonics.tamu.edu/university-consortium-for-applied-hypersonics-spring-forum-leaping-ahead/. Accessed May 13, 2022.

- Stone, Richard. “‘National pride is at stake.’ Russia, China, United States race to build hypersonic weapons.” Jan 8, 2020. https://www.science.org/content/article/national-pride-stake-russia-china-united-states-race-build-hypersonic-weapons. Accessed March 24, 2022.

- George Washington University. “General John E. Hyten, Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.” Oct. 28, 2021. https://nationalsecuritymedia.gwu.edu/project/general-john-e-hyten-vice-chairman-of-the-joint-chiefs-of-staff/. Accessed March 24, 2022.

- SBIR. “Hypersonics” https://www.sbir.gov/sbc/hypersonics. Undated. Accessed May 19, 2022.

- Cision PR Newswire. “Propulsion Company Ursa Major Delivers First-Ever Rocket Engines Qualified for Both Hypersonics and Space Launch Applications.” March 23, 2022. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/propulsion-company-ursa-major-delivers-first-ever-rocket-engines-qualified-for-both-hypersonics-and-space-launch-applications-301508664.html. Accessed May 23, 2022.

- Hicks, Bradley. “SBIR effort to enhance measurement of hypersonic wind tunnel velocities demonstrated at Tunnel 9”. Air Force Material Command. July 19, 2021. https://www.afmc.af.mil/News/Article-Display/Article/2699200/sbir-effort-to-enhance-measurement-of-hypersonic-wind-tunnel-velocities-demonst/. Accessed March 31, 2022.

- Army. “Army Hypersonics,” Oct. 8, 2021. https://www.army.mil/standto/archive/2021/10/08/. Accessed May 13, 2021.

- Congressional Research Service. “The U.S. Army’s Long-Range Hypersonic Weapon.” Dec. 8, 2021. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF11991. Accessed May 13, 2022.

- U.S. Army, “Dark Eagle is on the move: Soldiers complete New Equipment Training.” March 14, 2022. https://www.army.mil/article/254659/dark_eagle_is_on_the_move_soldiers_complete_new_equipment_training. Accessed May 20, 2022.

- U.S. Naval Institute. “Navy Can Install Hypersonic Missiles Aboard Zumwalt Destroyers Without Removing Gun Mounts.” March 16, 2022. https://news.usni.org/2022/03/14/navy-will-install-hypersonic-missiles-aboard-zumwalt-destroyers-without-removing-gun-mounts. Accessed May 12, 2022.

- Capaccio, Anthony. “Hypersonic-Missile Delay Puts U.S. Further Behind Russia and China” Bloomberg. April 6, 2022. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-04-06/hypersonic-missile-delay-puts-u-s-further-behind-russia-china. Accessed April 7, 2022.

- Air Force. “FY23 Budget Overview” March 28, 2022. https://media.defense.gov/2022/Mar/28/2002964733/-1/-1/1/FY%202023%20DAF%20BUDGET.PDF. Accessed May 13, 2022.

- Air Force, “Air Force conducts successful hypersonic weapon test.” May 16, 2022. https://www.af.mil/News/Article-Display/Article/3033416/air-force-conducts-successful-hypersonic-weapon-test/. Accessed May 20, 2022.

- Air Force. “Force Structure and Modernization Programs.” June 22, 2021. https://www.armed-services.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/SASC%20Airland%20Modernization%20Written%20Testimony_Final_OMB_Approved1.pdf. Accessed May 12, 2021.

- DARPA, “Second Successful Flight for DARPA Hypersonic Air-breathing Weapon Concept (HAWC)” April 5, 2022. https://www.darpa.mil/news-events/2022-04-05. Accessed May 13, 2022.

- Erbland, Peter, et al. “Tactical Boost Glide.” Undated. https://www.darpa.mil/program/tactical-boost-glide. Accessed March 24, 2022.

- Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency. “Operational Fires Program Completes Successful Rocket Engine Tests.” June 21, 2021. https://www.darpa.mil/news-events/2021-06-21. Accessed March 24, 2022.

- Department of Defense. “DoD Budget Request.” https://comptroller.defense.gov/Portals/45/Documents/defbudget/FY2023/FY2023_Budget_Request.pdf. March 28, 2022. Accessed March 28, 2022.

- Government Accountability Office. “Hypersonic Weapons.” March 2021. https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-21-378.pdf. Accessed March 23, 2022.

- Brockmans and Schiller. “A matter of speed? Understanding hypersonic missile systems.” Feb. 4, 2022. https://www.sipri.org/commentary/topical-backgrounder/2022/matter-speed-understanding-hypersonic-missile-systems. Accessed May 17, 2022.

- NASA, “Transiting from Air to Space: The North American X-15.” Undated. https://history.nasa.gov/hyperrev-x15/ch-0.html. Accessed May 18, 2022.

- The Boeing Co. “X-20 Dyna-Soar Space Vehicle.” Undated. https://www.boeing.com/history/products/x-20-dyna-soar.page. Accessed March 18, 2022.

- Air Force Academy. “Academy cadets team up with Air Force’s Office of Scientific Research to improve hypersonic systems” March 21, 2022. https://www.usafa.af.mil/News/News-Display/Article/2972849/academy-cadets-team-up-with-air-forces-office-of-scientific-research-to-improve/. Accessed March 22, 2022.

- Heppenheimer, T.A. “Facing the Heat Barrier: A History of Hypersonics,” September 2007. https://history.nasa.gov/sp4232.pdf. Accessed March 23, 2022.

- United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research. “Hypersonic Weapons.” Feb. 1, 2019. https://www.un.org/disarmament/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/hypersonic-weapons-study.pdf. Accessed March 22, 2022.

- Arms Control Association. “Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty at a Glance.” December 2020. https://www.armscontrol.org/factsheets/abmtreaty#:~:text=The%20United%20States%20and%20the%20Soviet%20Union%20ne gotiated%20the%20ABM,that%20the%20other%20might%20deploy. Accessed March 21, 2022.

- Arms Control Association. “Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty at a Glance.” December 2020. https://www.armscontrol.org/factsheets/abmtreaty. Accessed May 13, 2022.

- 100th Missile Defense Brigade. “Nation’s only missile defense brigade celebrates 15 years of dedicated service to homeland defense.” Oct. 25, 2018. https://co.ng.mil/News/Archives/Article/1672580/nations-only-missile-defense-brigade-celebrates-15-years-of-dedicated-service-t/. Accessed March 21, 2022.

- Missile Defense Agency. “Sea-Based Weapon Systems/Aegis BMD.” April, 2021. https://mda.mil/global/documents/pdf/seabased.pdf. Accessed March 21, 2022.

- Wood, Sgt. Sarah. “U.S. Missile Defense in Europe to Counter Rogue States.” Jan. 26, 2007. https://www.army.mil/article/1559/u_s_missile_defense_in_europe_to_counter_rogue_states . Accessed March 24, 2022.

- United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research. “Hypersonic Weapons.” Feb. 1, 2019. https://www.un.org/disarmament/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/hypersonic-weapons-study.pdf. Accessed March 22, 2022.

- Department of State. “London Naval Conference of 1930.” Undated. https://history.state.gov/milestones/1921-1936/london-naval-conf. Accessed May 13, 2022.

- Schwartz, Leonard, “Manned Orbiting Laboratory for war or peace?” January 1967. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2612515. Accessed March 24, 2022.

- United Nations. “Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT).” Undated. https://www.un.org/disarmament/wmd/nuclear/npt/. Accessed May 12, 2022.

- United Nations Office of Outer Space Affairs. “Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies.” Undated. https://www.unoosa.org/oosa/en/ourwork/spacelaw/treaties/introouterspacetreaty.html. Accessed March 19, 2022.

- Brooks, Peter. “China’s New Weapon Just Upped Global Threat Level.” Oct. 27, 2021. https://www.heritage.org/asia/commentary/chinas-new-weapon-just-upped-global-threat-level. Accessed March 25, 2022.

- Grego, Laura, et al. “Hyperventilating over Hypersonics,” Nov. 12, 2022. https://www.cfr.org/podcasts/hyperventilating-over-hypersonics. Accessed March 24, 2022.

- United Nations. “A Study Prepared on the Recommendation of the Secretary-General’s Advisory Board on Disarmament Matters.” February 2019. https://www.un.org/disarmament/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/hypersonic-weapons-study.pdf. Accessed May 13, 2022.

- People’s Daily Online. “AUKUS Plans Hypersonic Weapons to Confront China.” April 7, 2022. http://en.people.cn/n3/2022/0407/c90000-10080821.html. Accessed May 19, 2022.

- TASS. “Hypersonic Weapons to Comprise Backbone of Russia’s Conventional Deterrence Forces.” Feb. 9, 2021. https://tass.com/defense/1254191. Accessed May 13, 2021.

- Congress of the United States, “H.R. 2471.” March 17, 2022. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/BILLS-117hr2471enr/pdf/BILLS-117hr2471enr.pdf. Accessed March 17, 2022.

- Blinken, Anthony. “On the Extension of the New START Treaty with the Russian Federation, Feb. 3, 2021, https://www.state.gov/on-the-extension-of-the-new-start-treaty-with-the-russian-federation/. Accessed March 24, 2022.

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China. “Director-General of the Department of Arms Control of the Foreign Ministry Fu Cong Holds a Briefing for Chinese and Foreign Media on the Joint Statement of the Leaders of the Five Nuclear-Weapon States on Preventing Nuclear War.” Jan. 4, 2022. https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/eng/wjbxw/202201/t20220105_10478993.html. Accessed March 24, 2022.

- European Commission. “Commission Unveils Significant Actions to Contribute to European Defence, Boost Innovation and Address Strategic Dependencies.” Feb. 15, 2022. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_22_924. Accessed March 20, 2022.

- North Atlantic Treaty Organization. “Statement by NATO Heads of State and Government.” March 24, 2022. https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_193719.htm. Accessed March 25, 2022.

- Rolander, Niclas. “Global Military Spending Tops $2 Trillion for First Time as Europe Boosts Defenses.” April 24, 2022. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-04-24/military-spending-passes-2-trillion-as-europe-boosts-defenses. Accessed May 19, 2022.